The Francis Hopkinson Flag

Pictures of Hopkinson's house and grave Did Hopkinson design TWO flags?

|

#H235

$89.00 3X5' nylon with printed stars

and stripes, heading and grommets

Custom Made:

Appliquéd six-pointed stars and sewn stripes!

3'X5' with heading and grommets

Nylon $231

Cotton $232 Polyester $241 (The most

rugged but looks like cotton)

Custom Made:

Lead time can be 12+ weeks The Images Below are of the sewn nylon Francis Hopkinson Flag Francis Hopkinson Flag with Sewn Stars and Stripes

|

|

In September of 1990 we received a very unique letter. Earl P. Williams, Jr., a lecturer and author on the U.S. flag sent us the story of Frances Hopkinson, resident of Bordentown, N.J., signer of the Declaration of Independence, and apparent true designer of the American flag. The charming story which credits Betsy Ross as the creator of our national emblem was challenged in 1870, when it was first made public. However, we learned that it wasn't until 1917 that Hopkinson's biographer came across letters between Hopkinson and the Continental Congress which pointed to Hopkinson as the flag's creator. These letters are in the National Archives today. The pattern shown with 6 pointed stars is Earl's approximation of the flag Hopkinson designed in 1777. Scholars will likely continue to debate the exact appearance of our first national flag for years to come. There is no original example of the very first flag still left. No one can claim with certainty to know the exact appearance of the first flag. Our flag shows Earl's concept of the design based on his study. The Flag Guys® is proud to offer here the first Francis Hopkinson Flag commercially available. It is our response to our customers' requests that we do so in hopes of giving credit where credit is due. After reviewing the available evidence, it seems to me that Francis Hopkinson is the true designer of the American flag.

A Civil Servant Designed Our National Banner:

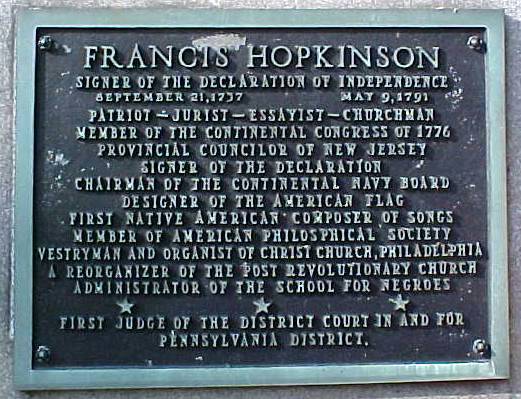

Born on October 2, 1737, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to English immigrants, Francis Hopkinson was the first graduate of the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania) in 1757. Hopkinson later studied law and set up his practice in Philadelphia. But his was not a career restricted to law and politics. He cultivated an appreciation for music, writing, heraldry, and art. After marrying Anne Borden, Hopkinson and his wife moved to Bordentown, New Jersey, her original home. In the summer of 1776, he was sent to the Continental Congress as a delegate from New Jersey. Among other things, he signed the Declaration of Independence and was appointed by President Washington as the first federal judge for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania on September 30, 1789. He was the only person to claim that he designed the United States flag. The U.S. Had a National Flag Before The Flag Resolution of 1777 From December 1775 to July 4, 1776, colonists used a "national" flag and ensign consisting of 13 alternating red and white stripes and the British union in the canton. This ensign was identical to the British East India Company's ensign of 1707 (author's note: some of the Company's ensigns had nine stripes, 13 stripes, or more). It was called the Continental Colors, among other things. Although unofficial, the Continental Colors also served as the national flag and naval ensign of the United States from July 4, 1776, until June 14, 1777. On the latter date, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution from its Marine Committee: "that the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation." In 1777, Hopkinson was the Chairman of the Navy Board's Middle Department; the Navy Board was under the Marine Committee. Three years later, while serving as the Continental Treasurer of Loans, he claimed that he designed the national flag/naval ensign of the United States. The fact that the Marine Committee entertained the Flag Resolution shows a connection between the Navy and the origin of the Stars and Stripes. Francis Hopkinson's "Labours of Fancy" On March 25, 1780, while serving as Treasurer of Loans, Francis Hopkinson became a consultant to the second congressional committee created to design a Great Seal of the United States because of his heraldic expertise. Congress had created the first of three such committees on July 4, 1776, because a seal was needed to denote America's sovereignty. An acceptable design was presented to Congress in 1782. The obverse of his designs were the first to incorporate elements from the Stars and Stripes. For example, in the obverse of both of his proposals, a cloud suspended above the shield encircled 13 six-pointed stars. In Hopkinson's second proposal, a Roman soldier (war) and female figure (peace) supported a shield carrying 13 alternating red and white stripes on a blue field. This proposal was submitted to Congress on May 10, 1780. Two weeks later, Hopkinson submitted an interesting letter to the Continental Admiralty Board (author's note: unlike today's Congress, which consists of a House of Representatives and Senate, the Continental Congress consisted of a legislative "branch" and administrative boards.). His letter stated that he had designed the United States flag, continental currency, a seal for the Admiralty and Treasury boards, and a Great Seal for the United States, among other things. Hopkinson referred to these designs as "Labours of Fancy." He further stated that although he made these designs free of charge, he would appreciate receiving a "Quarter cask of the public wine" from the government as a token of gratitude. In the opening of his letter, Hopkinson thanked the Board of Admiralty for just accepting his design for their seal. The Thursday, May 4, 1780, entry in the Journals of the Continental Congress described the seal. In part, "the arms (of the seal consisted of) thirteen bars mutually supporting each other, alternate red and white, in a blue field (emphasis added), and surmounting an anchor proper." Although not mentioned in his request, I discovered another proposed seal by Hopkinson. In 1987, while reading Standards and Colors of the American Revolution, by Edward W. Richardson, I recognized Hopkinson's handwriting under an anonymous drawing printed in the book. The drawing is a proposed seal for the Continental Board of War and Ordinance (see fig.) Hopkinson's handwriting states "N.B. If you (lose) this I will not draw another --." The board did not adopt the seal, but this drawing is highly significant because it contains the union of the 13-star flag. This flag is depicted in James Peale's painting entitled "The Battle of Princeton" and can be seen at the Valley Forge Historical Society. Scholars have been divided over what this flag was (viz., General Washington's flag as Commander-in-Chief, the flag of the General's Life Guard, or an artillery flag). An extant drawing of the proposed Stars and Stripes has not been found, so Hopkinson's drawing for the Board of War and Ordinance is the next closest thing. Hopkinson's drawing would have been executed in 1778 - only 1 year after the Flag Resolution was adopted -- because the board chose an entirely different design in 1778. Hopkinson's incorporation of motifs from the U.S. flag in his proposals for seals was a trademark. What did the early stars and stripes look like? During and immediately after the War, several sources indicate that the stars (estoiles) in the U.S. flag normally had six or eight points and were usually arranged in horizontal rows of 3-2-3-2-3 and 4-5-4. The U.S. Navy used the new national flag exclusively as its ensign instead of designing a different one (author's note: John Paul Jones sometimes used ensigns with red, white, and blue stripes in his squadron). On the basis of my research, the flag that Hopkinson designed approximates shown above. The Navy was accustomed to using ensigns with a 3-2-3-2-3 star pattern. The star pattern of the flag in Hopkinson's Board of War and Ordinance Seal (fig. 1) approximates this pattern. Like the stars in figure 1, the stars in figure 2 are also six-pointed. Further, both of Hopkinson's obverses of the Great Seal feature six-pointed stars (the stars in the early dies of the Great Seal were also six-pointed). (see fig. 2 next page) Hopkinson's idea to use stars to signify the union of states may have come from his coat of arms, the shield of which was emblazoned with three six-pointed stars on a chevron. The Reason Why Congress Rejected Hopkinson's Claim For Payment After Hopkinson sent his May 25, 1780, letter to the Board of Admiralty, the board forwarded it to Congress, which referred it to the auditor-general, who forwarded it to the Commissioners of the Chamber of Accounts. The commissioners felt that the account was legitimate and forwarded it to the Board of Treasury for payment in cash in lieu of the wine. Throughout the summer of 1780, Hopkinson's request was sent through various channels of red tape. Finally, on October 27, 1780, the Treasury Board presented their report to Congress. In the report, the board stated that Hopkinson was not the only person consulted on those designs that were incidental to the board and that in their opinion, civil servants such as Hopkinson already received adequate salaries and hence should not expect further compensation from Congress for such work. The matter was still unsettled during the following year, 1781. Hopkinson finally resigned from his position as Tresurer of Loans on July 23, 1781, in disgust. Thirty days later, Congress resolved "That the report relative to the fancy-work of F. Hopkinson ought not to be acted on." Because of this decision by Congress, some historians have hastily concluded that Hopkinson was not the only person who designed the Stars and Stripes. But to get a better understanding of why Congress rejected his claim, we must look at all of the pieces of the puzzle. The board did not refute the authorship of the designs that he made for them. Those works incidental to the Treasury Board were the Admiralty Board's seal, the United States flag, and the Great Seal of the United States. There is no evidence that anyone else designed the Admiralty Board's seal nor the United States Flag. But as stated earlier, Hopkinson was not the only person involved in the Great Seal project; 14 men were involved in the project from July 4, 1776 to June 20, 1782, although William Barton (a Philadelphia lawyer) and Charles Thomson (the Secretary of Congress) are normally credited. Further, Pierre Eugene Du Simitiere (an artist) was a consultant on the project before Hopkinson's involvement. Unlike Du Simitiere, Hopkinson, as Treasurer of Loans, was a civil servant; therefore, his services as a consultant were expected to be rendered free of charge as outlined in the Treasury Board's second objection. The Treasury Board's reference to "those exhibitions of Fancy" incidental to the board was apparently a reference to Hopkinson's drawings of the Great Seal. Therefore, if Hopkinson received the wine or payment, it would have also been for a design that had input from others. Although a drawing of the proposed design of the official Stars and Stripes has not been found, the overwhelming evidence suggests that Hopkinson designed the Stars and Stripes by himself. George E. Hastings, Hopkinson's first biographer, brought these facts to light almost 70 years ago. Throughout the United States, a movement is finally underway to reexamine Hopkinson's claim, and many historians, educators, public officials, organizations, and publications are now crediting Francis Hopkinson as the designer of the Stars and Stripes. In my opinion, this recognition is long overdue.

#2HOP Nylon $241 Cotton $242 Polyester $251 (The most rugged but looks like cotton) Custom Made: Lead time can be 12 weeks Or was this Hopkinson's design for our national flag? In 2012 Earl Williams published an article in NAVA News titled "Did Francis Hopkinson Design Two Flags?" Earl makes the case that the the flag shown here was his concept for our national flag and the design we sell at the top of this page was a naval flag. You can read Earl's article in NAVA News here

Earl P. Williams, Jr is a graduate of the University of Maryland (Arts and Sciences, 1973). Author of "What You Should Know About the American Flag" He is also the author of "Francis Hopkinson, Designer of the Stars and Stripes," NJ Historical Commission Newsletter, September 1989, and "The 'Fancy Work' of Francis Hopkinson: Did He Design the Stars and Stripes?" Prologue (Quarterly of the National Archives), Vol. 20, No. 1, Spring 1988, among other things. Mr. Williams is also the author of numerous articles on the U.S. flag and other aspects of American history, and he is a member of the North American Vexillological Association. |

|

INFO BIT: First Day Cover |

|

On June 14 (Flag Day) in 1992, the United States Postal Service honored Hopkinson as the "Father of the Stars and Stripes" with a commemorative pictorial postmark showing the flag seen above. The City of Philadelphia, Edward G. Rendell Mayor, issued a proclamation making September 21, 1992 Francis Hopkinson Day in honor of this "...great American leader" who "is also credited with designing the first official United States flag". Sept. 21 is Hopkinson's birthday.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Francis Hopkinson's sketch for a proposed seal for the Continental Board of War and Ordinance, 1778, featured 13 six-pointed starts on a solid field. This design had been used for the union of the Stars and Stripes in 1777. Photo: Earl P. Williams, Jr. - Nov. 1987 |

|

INFO BIT: State Resolution |

|

THE SENATE, State House, Trenton, NJ

State Resolution by Senator Haines

Whereas, the City of Bordentown in Burlington County is noted as a wellspring of American history, having played a majot role in the development of public education as the home of Clara Barton's first free school, in the fostering of pride in our country and its armed forces through the world famous Bordentown Military Institute, and in the creation of our most instantly recognized America symbol - the Stars and Stripes; and,

|

|

October 2, 1991

WHEREAS, those citizens whose contributions have redefined the course of this great nation's history are worthy of public praise and recognition; and

|

|

|

|

Francis Hopkinson home in Bordentown, NJ |

Francis Hopkinson House Bordentown NJ |

|

Today it is a law office to which this is the entrance |

|

|

Hopkinson's unmarked grave in Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia. Unmarked?! Yes indeed. I now know from my time spent as a volunteer guide there that the location of his grave is not known. Christ Church Burial Ground is the final resting place for about 4000 souls, but only about 1300 markers remain. The short broken marker to the left of Hopkinson's memorial stone indicated (with the flag) is known to be that of his daughter. The feeling is that |

Francis Hopkinson would likely have been buried with other family members and is therefore in that plot. There are a total of 5 signers of The Declaration of Independence in Christ Church Burial Ground including Benjamin Franklin. There are two other signers at Christ Church itself which is about a 5 minute walk away. |

|

Francis Hopkinson's memorial marker in Christ Church Burial Ground The url for this page is http://www.flagguys.com/hop.html 6/4/22 |

|