Page Title:

Union Flags of the War Between the States Confederate FlagsDefiant Flags Bennington Flags Betsy Ross

Civil War Flags North Historical Flags Washington Flags

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Black Union Soldiers in the Civil War (Not Available) By Hondon B. Hargrove: 250pp Hardcover, 6x9", 8pp photographs, tables, bibliography, index. This book refutes the historical slander that blacks did not fight in the war. The early opposition to using black soldiers is examined. Chapters include "This is a White Man's War," "The Emancipation Proclamation," and "Black Soldiers Prove Themselves Men." Topics covered include "Southern Negroes as Confederate Soldiers," "The Bureau for Colored Troops," "The Corps d'Afique," and "Shared Battles." Treatments of specific actions include the battles of Milliken's Bend, Fort Wagner, Olustee, Wilson's Wharf Landing (Fort Powhattan), Petersburg, The Crater, Fort Pillow Massacre (depending on whom you believe) and many others. Appendices include much information on the organization and statistics of black troops by regiment and descriptions of the actions resulting in The Congressional Medal of Honor being awarded to 16 black soldiers to whom this book is dedicated. "Very well researched...recommended to all students of military history." - Civil War; "excellent, scholarly analysis, complete with illustrations and numerous tables of figures to drive home his point." - AB Bookman's Weekly. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Captain William Driver - The Rest of the Story

By Devereaux Cannon, Jr.

The copyright for this article belongs to the author and is published here with his kind permission

Most North American vexillologists are familiar with the story of Captain William Driver, and his flag, ‘Old Glory’. There are several conflicting versions of his story. He was born 17 March 1803 in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and was apprenticed to a blacksmith for a time before he took to the sea. Most stories agree that he became a ship’s captain in 1824 at the young age of 21. Some say that his flag was presented to him by his mother in that year; other say that he received it in 1831 before setting sale as captain of the whaler Charles Doggett. In either case, the ensign he names ‘Old Glory’ would have been a flag of 24 stars.

His last voyage as a sea captain was in the year 1837. On his return to his home in Salem, he found Martha, his wife of ten years, stricken with throat cancer. She died in September of that year. After her death, he moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where his brother, Henry, was in business, taking with him his three young children and ‘Old Glory’. Shortly after moving to Nashville, 26 January 1838, he married Sarah Jane Parks, the 15 year old niece of his brother’s wife.

Captain Driver made his home at 158 South Summer Street, in what was then the separate municipality of South Nashville. The location is now known as 511 Fifth Avenue South, and the rather ugly residence currently on that site is not the original Driver home. He would often display ‘Old Glory’ on patriotic holidays, such as Independence Day and Washington’s Birthday, as well as his own birthday, by hoisting it on a cable which he ran across Summer Street from the upper level of his home to a pulley attached to a tree on the other side.

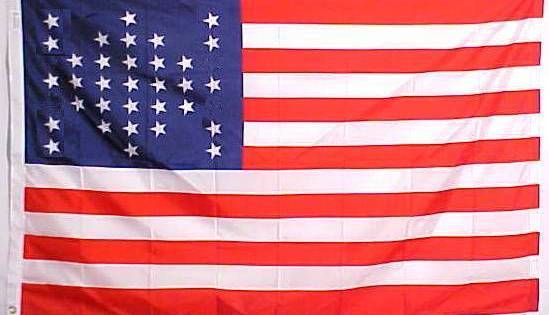

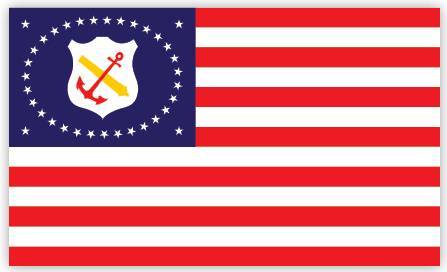

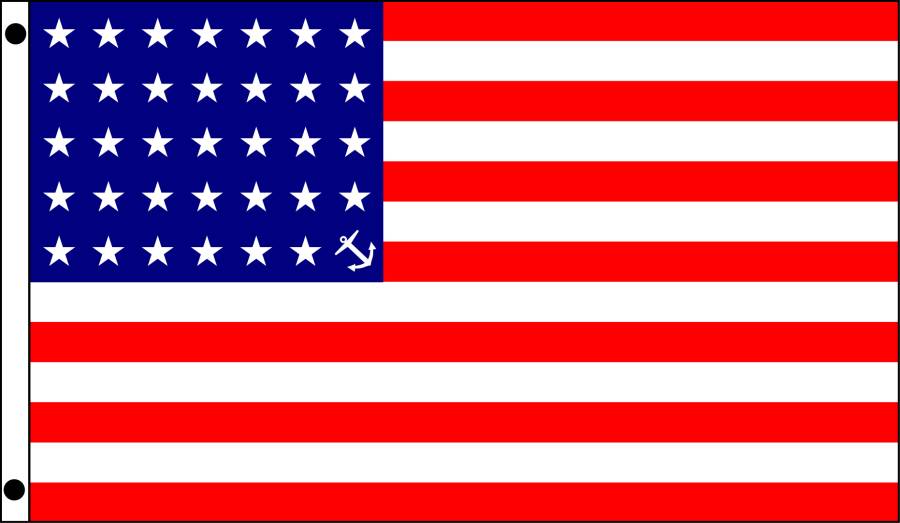

Sometime in 1860 or 1861, his wife and daughters took apart ‘Old Glory’, trimmed its rough edges, rebuilt it, and added stars to bring the total to 34. It is said that Captain Driver himself added the anchor in the lower fly corner of the canton. The 34th star would seem to argue in favor of an 1861 date, Kansas having been admitted to the Union in January of that year. However, Kansas statehood was eminent for some time, and the January 1861 admission was based on a state constitution that had been ratified by the people of the territory over a year before. So an 1860 date for a 34 star flag is not out of the question, even though that flag would not be official until 4 July 1861.

With Tennessee’s secession and admission to the Confederate States in 1861, Captain Driver, whose anti-secession sentiments were well known, found discretion to be the better part of valor, and hid ‘Old Glory’ inside a quilt or comforter according to most stories, in a chest according to others. Apparently two attempts were made to encourage him to surrender his flag, but each time he refused, and neither request was vigorously pursued. At least one other Nashvillian did continue to display the US flag, and she remained unmolested. However, she was the widow of a Mexican War veteran, and displayed her flag in memory of her husband rather than as a political expression.

With the fall of Fort Donelson in February 1862, Nashville became indefensible and was abandoned by the Confederate army. On Tuesday, 25 February 1862, as the last Confederate cavalry units withdrew from the city, the first Union infantry units took possession, and the national color of the 6th Ohio Infantry Regiment was displayed from the cupola above the Tennessee capitol building. Soon afterwards, at Captain Driver’s request, ‘Old Glory’ was raised on the capitol flag pole, which at the time was located on top of the pediment above the east entrance to the building.

The propaganda value of this story was too good not to use. With the capture of the first large city in a Confederate state, the first Southern capitol to be occupied had raised over it the ensign of a loyal New England sea captain who had been a resident of the Southern city for 24 years. Driver may have named his flag ‘Old Glory’ in 1824 or 1831, but it did not become an alternate name for the Stars and Stripes until after northern newspapers immortalized it following its hoisting over the Tennessee capitol in 1862.

The 1862 newspaper stories often portrayed Driver as a ‘frail old man’. That was stretching the truth a bit. In February 1862 he was just shy of his 59th birthday, barely four years older than Robert E. Lee. After the Union occupation of Nashville, he was an active part of the occupation government, and served as Provost Marshal of the city.

Driver was part of a minority of Union loyalist in Nashville. It turns out that he may also have held a minority view as such in his own family. A niece, Harriet Ruth Cooke, wrote in later years that Captain Driver hid ‘Old Glory’ with the help of Unionist neighbors, because he would not trust his secessionist family with it. It is this intra-family split that brings us to another part of the Driver story.

Nashville is now famous as Music City. In the 19th century, Nashville’s nickname was Rock City, a named now born by an unrelated tourist attraction near Chattanooga. The Nashville related name was said to have come about because one cannot dig more than a few inches without finding a solid sheet of limestone rock. Although Rock City is no longer a common alias for Nashville, it was so well established at one time that some business concerns in the city still use Rock City in their names.

The Rock City Guards was a militia company organized in Nashville in 1860. The organizers included lawyer Robert C. Foster, bookkeeper Frank Sevier, hardware merchant James B. Craighead, and salesman Joseph Vaulx. The middleclass nature of the incorporators was reflected in the ranks of the Rock City Guards.

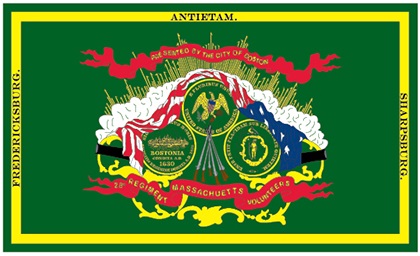

Two weeks after Fort Sumter was fired upon, the Rock City Guards had recruited so many additional men that it became a three company battalion, each company numbering 110 officers and men. Company B, under the command of Captain James B. Craighead, was the colour company of the battalion. Among the privates of Company B were George Wills Driver, the son of Captain William Driver, and William O. Driver, the son of Captain Driver’s brother, Henry.

On 23 April 1861, ‘amid great ceremony’, Fannie Claiborne presented a Confederate flag that she had made to Captain Claiborne and Company B of the Rock City Guards. On 8 May 1861 a second flag was presented to the company by Georgina Foster. Two days later Company B, with the two Driver cousins and these two flags, went into a camp of instruction at Allisonia, Tennessee, with the rest of the Rock City Guards as part of the First Regiment of Tennessee Volunteer Infantry. In July the Rock City Guards were in Virginia, and in September they were engaged in the Cheat Mountain campaign under the command of Robert E. Lee. During that campaign, one of the flags of the Rock City Guards was captured by an Ohio soldier. More than a century later, the descendants of that soldier gave the Rock City Guards flag to the Tennessee State Museum, were it currently resides.

At the same time that Captain Driver was hoisting ‘Old Glory’ over the Tennessee capitol, his son and nephew, with the rest of their regiment, were on their way back to Tennessee. Half of the First Tennessee Volunteers arrived at Corinth, Mississippi, early enough to take part in the battle of Shiloh, but the Rock City Guards did not arrived until the day after that battle was fought. At that time or shortly later, the regiment received a new battle flag of the pattern designed by General Leonidas Polk—blue with a white fimbrated red St. George’s style cross, charged with eleven white stars. It was under that flag that the Driver cousins took part in General Bragg’s Kentucky campaign, which culminated at the battle of Perryville on 9 October 1862. At that battle the Rock City Guards suffered approximately 50% casualties. Counted among those casualties were both of the Driver cousins. George Driver died on his wounds in a US Army hospital near Harrodsburg, Kentucky, and is buried in the Confederate section of Spring Hill Cemetery in that city. Captain Driver’s nephew, William O. Driver, recovered from his wounds, and died at the home of his daughter in Louisville, Kentucky in 1912.

The State of Wisconsin has long owned a Polk style battle flag which was attributed as being the flag of the First Tennessee Volunteers captured at Perryville by the First Wisconsin Infantry. This attribution has been called into doubt by the veterans of the First Tennessee themselves. Wisconsin loaned the flag to Tennessee early in the 20th century for a Confederate Veterans reunion. At that reunion, the First Tennessee veterans denied that the flag was theirs, saying that their flag has been torn to ribbons by the rifle and artillery fire that they endured at Perryville. The flag from Wisconsin is not very badly damaged. So it is likely that the flag under which Captain Driver’s son fought and died at Perryville no longer exists. But the flag owned by Wisconsin, which is now on loan to the Tennessee State Museum, is the same style and construction as that used by the First Tennessee.

There is another part of the Driver story that often goes untold, but one of which he was exceedingly proud. That is the story of his connection with Pitcairn Island.

The Pitcairn story begins with the famous mutiny of the crew of the HMS Bounty in 1789. The final destination of the mutineers and their Polynesian wives was Pitcairn Island, which they reached on 15 January 1790. There they lived cutoff from the outside world for 25 years, until their settlement was discovered by HMS Briton and HMS Tagus on 17 September 1814. By that time, the British Admiralty was not every interested in prosecuting the surviving mutineers. The Pitcairners, however, eventually desired emigration, and the islanders all set sail for Tahiti in March 1831.

They were welcomed by the Tahitians but they felt homesick. Soon, they began to suffer from infectious diseases, to which they had little immunity. Within a month of arrival in Tahiti, Fletcher Christian's son, Thursday October Christian, the first child born on Pitcairn and the oldest member of the community, died. His was the first of a heavy toll of deaths. Efforts were made to arrange for their return to Pitcairn. Finally, Captain William Driver of the Salem whaler Charles Doggett arrived at Tahiti and offered to take the remaining sixty-five Pitcairners back to their island home for a total of $500. A subscription was immediately organized by the community to which the Pitcairners contributed by selling blankets and other necessities. Captain Driver sailed with them from Tahiti on 14 August 1831, and reached Pitcairn on 3 September. Some sources say that Driver lost money for his ship’s owner’s on this mission, and that he lost command because of it. The fact that he did not retire from the sea until six years later, however, seems to belie that tale.

Captain Driver was proud of his action regarding Pitcairn Island, so much so that he left two monuments to it. One was in the name of his last born son. Thomas Pitcairn Driver was born in Nashville on 10 September 1858. Sadly, he died nine months later, and is now buried in City Cemetery near his famous father. The other monument is Driver’s own tombstone. This stone was design by Driver himself several years before his death in 1886. It is in the form of a tree trunk with a ship's anchor carved on one side. The inscription reads: ‘A master mariner; sailed twice around the world; once around Australia; removed the Pitcairn people from sickness and death in Taheita (sic) to their own home on September 3, 1831. Then sixty in number, now twelve hundred.’ Near the preceding inscriptions are the words: ‘Trust in the Lord and do good; so shalt thou dwell in the land, and verily shalt thou be fed.’ Toward the bottom is carved: ‘I never wanted since and ‘His God, his country, his ship and his flag, "Old Glory."’. While Captain Driver died almost 100 years before Pitcairn Island had a flag of its own, the Pitcairn flag should be a prominent feature of any Vexillological discussion of Captain William Driver.

This is the Nashville grave of William Driver 1803-1886. He rests in the Nashville City Cemetery along with other family members.

He sailed around the world twice and around Australia once. In 1831 he rescued the descendants of the survivors of the HMS Bounty from Tahiti.

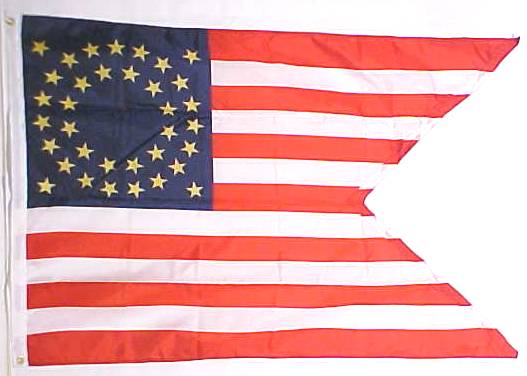

"Old Glory"

Massachusetts sea captain William Driver named his personal flag Old Glory. This is his flag as it appeared around 1861 after his daughters updated his original 24 star version with which he sailed the seven seas. Note the anchor in the lower right corner of the canton. Retired in Nashville, during The War Between The States, his pro Union stance necessitated that he hide his flag. Some say attempts by Confederate citizens to take it required this action. Some say he had to hide it from his own secessionist family members! When Union troops occupied Nashville in 1862, Driver asked them to fly Old Glory over the Capitol building for all to see. They did. This transplanted Yankee's flag flying over the first large Southern city to be captured was popularized in Northern newspapers and led to the widespread and beloved nickname for the American flag. His original flag is in The Smithsonian Institution and measures about 9x15 feet.

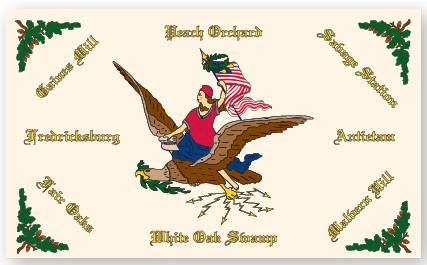

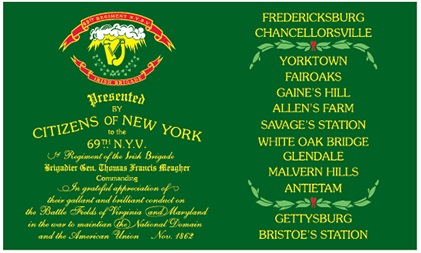

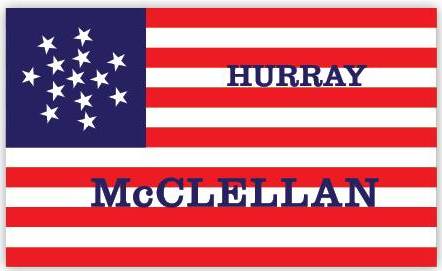

Meanwhile George Driver, the Captain's son, was serving as a Confederate private in The Rock City Guards, a Nashville militia battalion which would become part of the 1st Regiment of Tennessee Volunteers. Their flag appears at left. According to the 11/26/05 posting on Mr. Cannon's web "The flag was made in April 1861, after Virginia joined the Confederacy as its 8th state, but before Tennessee formally seceded. Tennessee is represented at the 9th star outside the circle, representing that we weren't in the fold yet, but were on the way. The original flag measures about 3 feet wide and almost 7 feet long, and is in the Tennessee State Museum." George died of wounds suffered at Perryville.

`Copyright 1996-2020 THE FLAG GUYS ®

The following are proprietary trademarks, service marks and/or trade names of Old Windsor Distributors, Inc.:

The Flag Guys®; The Flag GuyTM, Li'l SamSM, The Li'l Sam cowboy character, The term Vexibee and the Vexibee Character

Where They Still Say "Yes Sir", "Yes, Ma'am" and "Thank You For Your Business."®, Iron ManTM and EagleTM