Page Title: George Washington's Flags

|

Defiant Flags Bennington Flags Betsy Ross Civil War Flags North Historical Flags Washington Flags

George

Washington's Personal Flag George Washington's Headquarters Flag 1775

#H34 $102.00

Commander In Chief Flag 3x5' Dyed Nylon

#H233

$102.00

On March 11, 1776 The Continental Congress authorized organized a bodyguard and

personal escort unit to Gen. George Washington. Congress frowned on such titles as "His Excellency's Guard" and

"Washington's Life Guard" because they seemed to mirror the British titles of

nobility which were being rejected as part of the revolutionary mindset. In

April 1777 the Second Continental Congress warned that the use of such monikers

in official communications was prohibited but their usage persisted.

|

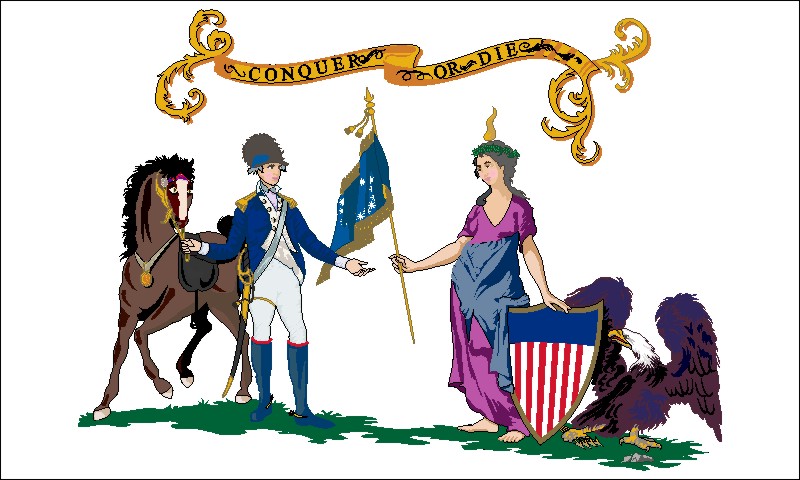

Washington's Life Guard Flag #H143 $89.00 3x5' Dyed Nylon with heading and grommets Officially called The Commander-in-Chief's Guard, the unit was authorized in 1776 and disbanded 1783 right here in Newburgh, NY. At its peak it had about 250 men whose function was to protect The General as well as the money, baggage and important papers of his command. It was also tasked with provisioning his HQ. The guard was with him in all of his battles and sometimes was sent into combat. It was an honor to belong to this volunteer unit and care was taken to include men from all 13 states. There was a height requirement of 5'8" to 5'10". Men were to be "sober, intelligent, and reliable", "honest, clean, neat and spruce," even "handsome, well made and of good behavior." These were clearly a squared away bunch of guys. No rookies were allowed. There was a requirement that candidates be already "drilled". The unit's motto, "Conquer or Die" adorns the flag. Lady Liberty passes a flag to a guard member.

|

Background: Washington anticipated that the British would try to take New

York and he had moved his army there. He was correct. On June 29th the British

fleet was sighted. Within a week there were 130 ships anchored off Staten Island

and on July 2nd they landed troops there. For almost two months

ships continued to arrive until they finally totaled 400. 32,000 troops

eventually landed.

On August 27, 1776, the largest battle of the Revolution began. Variously called

the Battle of Long Island or the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, it was the

first battle fought

by the Untied States Army on behalf of the now independent United States of

America. If the Royal Navy is included, Washington's little army of 10,000

largely green troops faced a force of 40,000 British and Hessians. He also had

no navy.

The Americans were flanked, attacked from the rear and routed. During the

action, 250 Marylanders stayed behind and attacked the British six times in

order to buy time for their comrades in arms to escape across a marsh. The

Marylanders were annihilated. Washington's army was left huddled and dug in on

the Brooklyn shore- the water at their back and the British in their front. With

a dramatic and dangerous night time evacuation, Washington's army lived to fight

another day. The wind cooperated by preventing the British fleet from sailing up

the East river to surround the Americans. Towards dawn, a sudden and heavy fog

set in to conceal the completion of the evacuation. The British were stunned to

find the Americans had escaped to Manhattan.

As he to prepared his troops for what was to come, George Washington

called on them to

do their duty, think of posterity- that is you and me- keep their powder dry,

remain disciplined and to sleep with their weapons.

George Washington, General Orders

Head Quarters, New York, July 2, 1776

"The time is now near at hand which must probably determine, whether Americans

are to be, Freemen,

or Slaves; whether they are to have any property they can call their own;

whether their Houses, and

Farms, are to be pillaged and destroyed, and they consigned to a State of

Wretchedness from which no

human efforts will probably deliver them. The fate of unborn Millions will now

depend, under God, on

the Courage and Conduct of this army--Our cruel and unrelenting Enemy leaves us

no choice but a

brave resistance, or the most abject submission; this is all we can expect--We

have therefore to

resolve to conquer or die: Our own Country's Honor, all call upon us for a

vigorous and manly

exertion, and if we now shamefully fail, we shall become infamous to the whole

world. Let us

therefore rely upon the goodness of the Cause, and the aid of the supreme Being,

in whose hands

Victory is, to animate and encourage us to great and noble Actions--The Eyes of

all our Countrymen

are now upon us, and we shall have their blessings, and praises, if happily we

are the instruments

of saving them from the Tyranny meditated against them. Let us therefore animate

and encourage each

other, and shew the whole world, that a Freeman contending for LIBERTY on his

own ground is superior

to any slavish mercenary on earth.

The General recommends to the officers great coolness in time of action, and to

the soldiers a

strict attention and obedience with a becoming firmness and spirit.

Any officer, or soldier, or any particular Corps, distinguishing themselves by

any acts of bravery,

and courage, will assuredly meet with notice and rewards; and on the other hand,

those who behave

ill, will as certainly be exposed and punished-- The General being resolved, as

well for the Honor

and Safety of the Country, as Army, to shew no favour to such as refuse, or

neglect their duty at so

important a crisis.

The General expressly orders that no officer, or soldier, on any pretence

whatever, without leave in

writing, from the commanding officer of the regiment, do leave the parade, so as

to be out of

drum-call, in case of an alarm, which may be hourly expected--The Regiments are

immediately to be

under Arms on their respective parades, and should any be absent they will be

severely punished--The

whole Army to be at their Alarm posts completely equipped to morrow, a little

before day--

As there is a probability of Rain, the General strongly recommends to the

officers, to pay

particular attention, to their Men's arms and ammunition, that neither may be

damaged--

EVENING ORDERS

'Tis the General's desire that the men lay upon their Arms in their tents and

quarters, ready to

turn out at a moments warning, as their is the greatest likelihood of it."

March 15, 1782, The Newburgh Conspiracy

It Happened in Our Town. Mutiny could have shattered the American Revolution. In New Windsor, New York, George Washington, The Father of Our Country, by the sheer persuasion of his person and of his words, saved the cause. He responds to the "Newburgh Addresses"

The following is from

George Washinton's Newburgh Address A Massachusetts Historical Society Picture Book

The text shown in Italics is taken verbatim.

It should be noted that at the time, Washington's Headquarters, where he lived with his wife and staff, was in Newburgh, NY, some two or three miles away. He delivered his address in New Windsor at the site where The Continental Army that he commanded, consisting of some 5,000 soldiers, had its last encampment.

After Cornwallis surrendered his army at Yorktown, Virginia, the British still had a major force in New York City. Washington positioned his army 60 miles up the Hudson River in our town of New Windsor, New York. This position made him available to protect West Point, the Key to the Continent, and allowed him to keep the British in check while the world waited to see what the peace talks in Europe would bring. What would happen next? Would peace be negotiated? Would the British force in New York march on somewhere else? Would a group of disgruntled officers doom the entire enterprise?

Washington's Headquarters, the New Windsor Cantonment, The Last Encampment of The Continental Army, Knox's Headquarters, and The Edminston House may be visited today

In December 1782, fourteen principal officers of the Continental army in winter quarters at Newburgh, New York, headed by Major-General Henry Knox, signed an Address to the continental Congress entreating it to pay part of the back pay due them and the soldiers, make provision for future payment of the balance, and vote "full pay for a certain number of years, or for a sum in gross, as shall be agreed to by the committee sent with the address," instead of half-pay for life which the Congress had voted in October 1780 to retired officers. The existing provision as to retirement pay had been widely condemned, and the officers presumably supposed that the proposed new arrangement would have the twofold advantage of being less unpopular and by fixing the precise amount of future compensation, of uniting their influence with that of the many other public creditors having claims of specific amounts.

The officers and men had been guaranteed money and benefits by congress. Now they were offering to settle for less than congress had promised them in the hopes that the lesser amount would get more support in light of the many other obligations to which congress had committed itself; a half loaf is better than none at all.

The committee referred to in the address-consisting of Major-General Alexander McDougall of New York, Colonel Mathias Ogden of New Jersey, and Lieutenant-Colonel John Brooks of Massachusetts-promptly presented the Address to the Congress, which had been given notice of the affair by letter from Washington to Joseph Jones, one of the Virginia delegates, informing him of the Address, which, had been given notice of the affair by a letter from Washington to Joseph Jones, one of the Virginia delegates, informing him of the Address, which, "tho' unpleasing is just now unavoidable," because of the "variety of discontents" prevailing in the army.

General Washington had warned one of the Virginia delegates to congress that the grievances were a "bummer" but that they could no longer be overlooked given the discontent prevailing within the army.

The Committee found the bankrupt congress willing to do the little it could to meet the requests in the Address except in the matter of pay for retired officers, of whom there would soon be many hundreds more when the approaching peace led to the disbanding or drastic reduction of the army.

The committee found out that congress had no money and would not meet the commitment it had made except in the case of the retiring officer corps, which would grow in ranks due to the outbreak of peace.

...the delegations from the three states which had opposed the original commitment, with the addition of Rhode Island, voted against and thus defeated the proposal, which, under the Articles of Confederation, could be carried only by the affirmative votes of nine states.

But when put to a vote, congress said "no dice."

On receipt of news of this defeat, a group of officers at Newburgh, with Major John Armstrong of Pennsylvania acting as their penman, circulated an anonymous paper calling a meeting of officers to be held at a recently erected building known as "the Newbuilding" at 12 o'clock noon on March 11, 1783. Deeming it wise to permit such a meeting but to regularize it, Washington, on learning of the anonymous call, included in his general orders for the day of March 11 a passage denouncing the proposed "disorderly" meeting but requesting that "the General and Field officers with one officer from each company and a proper representative of the staff of the Army will assemble at 12 o'clock on Saturday next [March 15] at the Newbuilding to hear the report of the Committee of the Army to Congress" and to "devise what further measures ought to be adopted as most rational and best calculated to attain the just and important object in view.

When congress reneged, some army officers bucked the chain of command and army protocol. They called an illegal meeting to plan their next move. Washington diffused the situation by calling his own meeting.

This action scotched the unauthorized meeting on March 11; but, nothing daunted, Armstrong now circulated another anonymous paper, in effect urging the officers to demand instead of to ask for the things they had originally requested, with the addition of an implied threat that if all their demands were not satisfied they would compel the Congress to accede to them.

When Washington took the wind out of their sails, the disgruntled officers upped the ante by threatening to force congress to give them what they wanted. After all, the army had the guns and the power to march on congress! Military coups happen all the time! The army could simply march on congress.

Alarmed by this paper, Washington attended the meeting which he had called for March 15 and there read he famous address here reproduced. ( See below.)

"His Execellency." wrote Captain Samuel Shaw a few weeks later, "after reading the first paragraph, made a short pause, took out his spectacles, and begged the indulgence of his audience while he put them on, observing at the same time, that he had grown gray in their service, and now found himself growing blind. There was something so natural, so unaffected, in this appeal, as rendered it superior to the most studied oratory; it forced its way to the heart, and you might see sensibility moisten every eye. The General, having finished, took leave of the assembly, and the business of the day was conducted in the manner which is related in the [published] account of the proceedings."

When Washington addressed the tension filled room, (the very building has been reproduced for your visitation), the aged warrior paused after a few words and said as he took out his glasses, "you will forgive me, but I have not only grown gray but also blind in the service of my country." The sight of the venerable leader struggling with his eyesight in the endeavor of persuading his forces to remain loyal to the civilian authority left not a dry eye in the house.

Washington's address was completely successful. The assembled officers adopted resolutions denouncing 'the secret attempts... to collect the officers together in a manner totally subversive of all discipline and good order," expressing confidence that the Congress would not disband the army without acceding to the officers' original requests (including an acceptable arrangement for "half-pay, or commutation of it"), and requesting Washington to write the President of Congress, "earnestly entreating the more speedy decision of that honorable body." Washington wrote as requested, and Congress promptly responded favorably by voting (nine states to three) that retired officers of any regiment, if a majority so elected, should have full pay for five years instead of half-pay for life.

Washington won over the crowd of officers who soundly rejected the proposal to usurp authority. They urged him to write to congress on their behalf. He did write and won a favorable result.